New coursing laws avoid the ‘H’ word

Why is the Hunting Act 'too political'?

Farmers Weekly reported on 23rd June 2021 that “tougher penalties will be introduced” for illegal hare coursing. New legislation proposed by Defra, according to Farmers Weekly, include:

Amendment of the Game Act 1831 and Night Poaching Act 1828 to increase fines and introduce custodial sentencing.

Create a new offence of “going equipped” for illegal hare coursing.

Enable police to reclaim the cost of seized coursing hounds.

The announcement came a week after Conservative MP Richard Fuller submitted a Private Member’s Bill on illegal coursing. On 16th June, Fuller wrote on his website that he “will seek changes to give police the tools they need to do the job”. His suggestions reflect those proposed by Defra.

Both of these come hot on the heels of the government’s action plan for animal welfare, published 12th May. The plan specifically highlights the issue of illegal hare coursing and says it will “provide law enforcement with more tools to address the issue effectively”.

The new powers will come as part of the sweeping Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill. And they are notable for side-stepping amendments to the other anti-coursing legislation, the Hunting Act 2004.

Misrepresenting the Hunting Act

During a 1st December 2020 parliamentary debate on the issue of laws on coursing, Conservative MP Gordon Henderson said hare coursing:

was an offence of its own long before the Hunting Act 2004 came into force. I share the view of the Nation Farmers Union (NFU) [sic] and see no reason why the Hunting Act 2004 should have to be used to sort out this problem.

In a March 2020 post on its website, the NFU says that the Hunting Act’s “powers are difficult for police to use in practice”. Instead, it supports “simple” changes to the Game Act.

Henderson also points out that Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) guidance says the Game Act and Night Poaching Act are the most effective tools for tackling illegal coursing. The CPS website says:

Where trespass to land is an ingredient of the activity said to constitute an offence under section 1 or section 5 of the Hunting Act 2004, it will generally be easier to continue to prosecute under the Game Acts.

But this is built on section 5 not capturing “recreational” coursing in its wording. In fact, the CPS guidance goes on to say that “strong supporting evidence of competitive elements such as betting on the outcome” make prosecuting coursers with the Hunting Act easier. And betting forms a key component of the argument by those lobbying to change laws on coursing. The Country Land and Business Association, one of the new legislation’s lead lobby groups, even highlights illegal betting in its statement on the legislation.

What about the data?

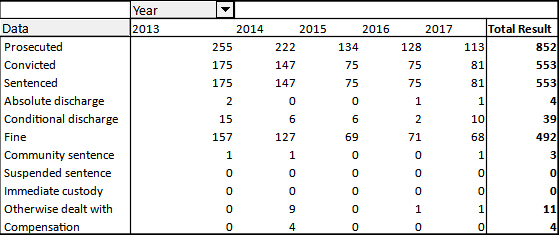

Ministry of Justice data shows that between the start of 2013 and end of 2017 there were convictions of 553 people under the Game Act 1831. Of these, 492 resulted in fines.

And during the same period, the same dataset shows convictions of 189 people for offences under the Hunting Act 2004. Of these, 169 resulted in fines.

That means the Hunting Act provides about 34% of the number of convictions that the Game Act does. There doesn’t appear to be conviction rate data publicly available for the Night Poaching Act, but a freedom of information request shows that during the same period (2013 to 2017) a total of 259 people were “proceeded against” under the law.

A 2019 government document on wildlife crime said that 474 individuals were convicted under the Hunting Act between its introduction and the end of December 2017. And according to a table of completed prosecutions drawn up by Protect Our Wild Animals (POWA), there were 34 individuals from hunting packs convicted during the same period. That means 440 convictions, or nearly 93% of convictions, under the Hunting Act were for coursing. Meanwhile, a thesis by University College London PhD candidate Dorothea Delpech states that there were a total of 2,065 people successfully prosecuted for “Night & Day Poaching” between 2004 and 2014, which includes both 19th Century Acts.

The number of prosecutions under the Hunting Act is clearly far fewer than those under the two poaching laws.

On the other hand, the average fine for Hunting Act offences until 2020 was £541 according to POWA. Meanwhile, according to Delpech, the average fine for offences under the Game Act amounted to £227 between 2004 and 2014. So there appears to be some vitality in the Hunting Act.

“Unenforceable”

From the outset, one key argument used by those opposing the Hunting Act is that it is an unenforceable law. Delly Everard, then the Wessex regional director of the Countryside Alliance, said at the time the Act came into force that it is “ridiculous and unenforceable”. And it has remained part of the hunting industry’s discourse until today.

Beyond the hunting industry, senior police chiefs made similar claims when the ban was introduced according to SomersetLive. The narrative is also part of Tory rhetoric, such as Mid-Norfolk MP George Freeman who described the law in 2007 as “unenforceable”. And even Defra itself described the law in 2010 as not having “demonstrable success” because it is “difficult to enforce”.

With the weight of the hunting industry and various agents of the State stacked against it, it’s no surprise that the Hunting Act has struggled to stay afloat.

Answering the question of why those with power favour poaching laws over hunting laws to battle hare coursing is beyond the scope of this article. But a comment by Dominick Dyer, writer and wildlife campaigner, may put things into perspective. In an episode of Off the Leash podcast, Dyer discusses the recently published animal welfare action plan, and specifically its commitment to greater efforts in dealing with hare coursers. Dyer then goes on to say:

But that begs the question: if you're going to do it for coursing, why aren't you going to do it for fox hunting? Or the hunting of hares with hounds? The hunting of deer and stag with hounds? ... I raised that with the officials in the meeting we had with Lord Goldsmith, and they said 'well that's political, and we've not been given a remit to go down that route'.

The Citro contacted both Defra and Goldsmith’s office for comment specifically on why the Hunting Act is ‘too political’. Goldsmith’s office didn’t reply, but a spokesperson for Defra offered the following response:

Crimes such as hare coursing and deer poaching are completely unacceptable. This government is committed to working closely with the police to tackle criminal activity and make rural areas safer places to live and work.

We are clear that those found guilty of these activities should be subject to the full force of the law, with unlimited fines already in place for anyone breaching the Hunting Act.

Dyer provided The Citro with further details on the contention between government ministers and the Hunting Act, saying:

I made it clear that any attempt to come down hard on hare coursing under pressure from farmers and landowners, whilst taking no action against hunts which also kill hares with hounds, would show the Government is hugely inconsistent when it comes to protecting wildlife.

This is a view increasingly held by Tory back benchers, Defra Minister Lord Goldsmith and the Prime Ministers wife Carrie Johnson, who was a key player in ensuring the Tory Party jettisoned the Hunting Act Repeal Commitment in the 2019 manifesto.

Dyer’s full statement to The Citro can be read here.

Sore spot

Data shows the Game Act and Night Poaching Act have historically been more effective in achieving prosecutions against hare coursers. On the other hand, the potential of the Hunting Act in delivering greater penalties is also evident – especially as it’s already imbued with the power of unlimited fines. That then brings forth another question: why not strengthen the Hunting Act, rather than 19th Century poaching laws?

Campaign group Action Against Hare Hunting reacted similarly to the announcement of the new laws, saying it:

believes creating extra legislation for coursing, while doing nothing to strengthen the Hunting Act, will only increase the confusion surrounding the legality and policing of both types of hare hunting.

The locus of the poaching laws is distinctly different from that of the Hunting Act. Where the two 19th Century acts place the weight of criminality on transgressions against private property, the hunting ban seeks to alleviate cruelty against wildlife. The latter, of course, is a far greater threat to the hunting industry than the former. And given the hunting industry’s representation throughout the organs of the State, that may be a sore spot or, indeed, ‘too political’.

Want to support The Citro? Click here to contribute.

Main image via Wikimedia Commons